Archives des nouvelles

Die Another Way: Finding sustainability and reciprocity in death

- Détails

- Publié le jeudi 11 septembre 2025 10:16

By Rachael Young

September 15, 2025

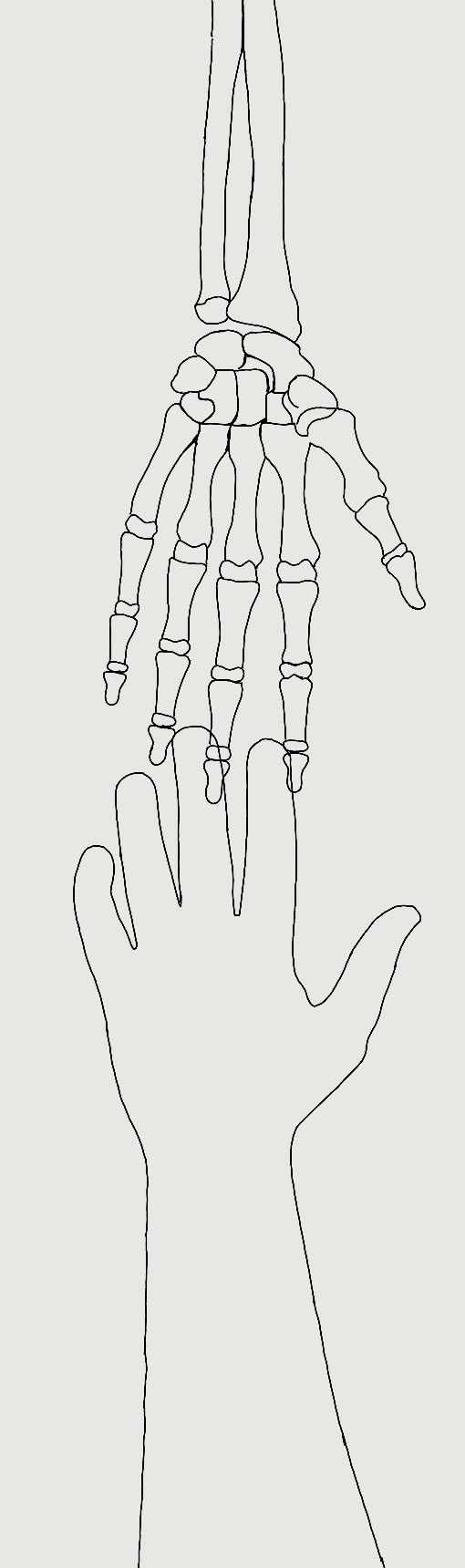

With a scalpel in hand, I inspected the palm in front of me closely. Stealing a glance to my textbook, I took a deep breath and began to cut. Methodically, I parsed apart layers of skin and fascia, eyes always seeking the intricate network of muscles, tendons and nerves that lay just below. Tracing around delicate wrinkles, I advanced slowly toward the fingertips. Despite the shakiness of my unpracticed hand, it was peaceful, and my mind began to wander. This was not the first time I’d dissected in the cadaver lab, but at just a few weeks into my intro anatomy course, I was still uncertain. Uncertain about what tools to use, uncertain about how to find the tiny nerves that would appear on my exam, and above all, uncertain about how to feel.

With a scalpel in hand, I inspected the palm in front of me closely. Stealing a glance to my textbook, I took a deep breath and began to cut. Methodically, I parsed apart layers of skin and fascia, eyes always seeking the intricate network of muscles, tendons and nerves that lay just below. Tracing around delicate wrinkles, I advanced slowly toward the fingertips. Despite the shakiness of my unpracticed hand, it was peaceful, and my mind began to wander. This was not the first time I’d dissected in the cadaver lab, but at just a few weeks into my intro anatomy course, I was still uncertain. Uncertain about what tools to use, uncertain about how to find the tiny nerves that would appear on my exam, and above all, uncertain about how to feel.

I had a strange relationship with the body in front of me. In some ways, I knew this person more intimately than anyone had known them in life. I had literally seen the depths of their heart, but I didn’t know their name. I was the last person to ever hold their hand. Who was the first, I wondered. Had this hand played an instrument, worn a wedding ring, cradled a child? I will never know. The only thing I am sure of, is that this person’s final act in life was to give themselves completely to others in death. It was comforting to witness death as a gift like this. I felt less uncertain, and more grateful.

My focus eventually returned to the dissection. By the end of lab, I’d revealed much of the palmar surface; I could name and identify every muscle, artery, tendon, nerve, and bone that was tested on the midterm. I’ve since forgotten much of this anatomy, but I remember the feeling of holding that hand. I remember the way it held mine back. I remember the space it gave me to reflect on the impact of our bodies after we die.

Outside of these rather one-sided conversations in cadaver labs, I find that good discussions about death can be hard to come by. In the rare cases when we are encouraged to talk about death, the focus is often on practicalities or the psychological benefits of doing so. While I recognize the importance of these approaches, there is a more pressing issue that should motivate us to prioritize this dialogue; our death rituals are harming ecosystems globally1. Over 300,000 people die every year in Canada2, the vast majority are either cremated, or embalmed and buried3. Both of these practices exacerbate existing threats to human and more than human life1.

Cremation is the most common death practice in Canada3, and it is a source of several concerning emissions4,5. In the cremation process, carbon dioxide is released from the natural gases burned to power furnaces as well as from the organic carbon stored in human bodies1. This contributes to the global greenhouse gas effect and ongoing climate crisis, but there are further hazards still. Compounds that accumulate in the human body such as heavy metals like mercury, volatile organic compounds like benzene, and other concerning chemicals, are routinely emitted during cremation5. A study in British Colombia, for example, found that crematoriums accounted for over 7% of atmospheric mercury emissions in the province6. Once released, these pollutants may enter any part of the ecosystem and endanger the health of many living things5.

Like cremation, traditional embalming and burial practices produce a number of harmful environmental impacts1. After burial, heavy metals, pathogens, and hazardous chemicals from embalming, like formaldehyde, leach from bodies into the surrounding soil7–9. Eventually, these pollutants enter ground water systems, and spread throughout the ecosystem7,9. Then, there are the materials involved in the process. From coffins to grave markers, resources are extracted and may be transported long distances to complete the burial process1. There are also land-use concerns. Cemeteries can take up large areas, which may contribute to habitat fragmentation and other ecological concerns10. Grass lawns are common and require large amounts of water while contributing little to biodiversity1,10. Together, these factors have concerning implications for the health and well-being for humans, animals and plants alike.

In recent years, green burial practices have emerged as a potential solution to these challenges1,10. While there are promising options like water cremations that reduce harmful emissions, natural burials, and traditional Indigenous practices, there remain significant challenges1,10. These alternatives are often expensive, inaccessible, or not legally recognized under colonial systems10. Complex social, cultural, and religious practices may also impact choices around death1. So how do we make sustainable, lasting changes? Beyond small steps like opting for alternative cremation, avoiding embalming and choosing local, natural materials for grave markers, I don’t think there is a simple answer. I do, however believe that talking more openly about death and the impacts of death practices on ecosystems is a good place to start.

Conversations about death can be hard, but I often find them easier when I think back to my experiences in the human anatomy lab at the University of Guelph. It’s difficult to articulate what a privilege it was to learn from the body donors. I can confidently say that over the two years I spent in the anatomy program, they taught me far more than just the structure and function of the human body. I cannot thank someone who is dead, so instead I find myself asking how I can give to others like they gave to me; I invite you to do the same. How can we make our deaths and death practices more sustainable? How can we become more like the hand that held mine when I was so uncertain? How can we turn death into a gift for all living things?

References

1. Nosi, C., D’Agostino, A., Ceccotti, F. & Sfodera, F. Green funerals: Technological innovations and societal shifts toward sustainable death care practices. Technol Forecast Soc Change 207, 123644 (2024).

2. Deaths, by month. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310070801.

3. Industry Statistical Information - Cremation Association of North America (CANA). https://www.cremationassociation.org/industrystatistics.html.

4. Xue, Y. et al. Emission characteristics of harmful air pollutants from cremators in Beijing, China. PLoS One 13, e0194226 (2018).

5. Mari, M. & Domingo, J. L. Toxic emissions from crematories: A review. Environ Int 36, 131–137 (2010).

6. Piagno, H. & Afshari, R. Mercury from crematoriums: human health risk assessment and estimate of total emissions in British Columbia. Can J Public Health 111, 1011 (2020).

7. Zychowski, J. Impact of cemeteries on groundwater chemistry: A review. Catena (Amst) 93, 29–37 (2012).

8. Ezenwa, I. M. et al. Burial leakage: A human accustomed groundwater contaminant sources and health hazards study near cemeteries in Benin City, Nigeria. PLoS One 18, e0292008 (2023).

9. Zychowski, J. & Bryndal, T. Impact of cemeteries on groundwater contamination by bacteria and viruses – a review. J Water Health 13, 285–301 (2015).

10. Green end-of-life options - David Suzuki Foundation. https://davidsuzuki.org/living-green/green-end-of-life-options/.