News Archive

Healthpunk Vol 2

- 15 DECEMBER 2022

By Filip Maric, Liv Johanne Nikolaisen, Mahitsonge Nomusa Ntinga, Jena Webb

'Tis the season to imagine new ways forward for more ecologically and socially responsible healthcare futures! One year after the publication of Physiopunk Vol 1, we are happy to share Healthpunk Vol 2: Fiction + Healthcare + You, A collection boasting ten Healthpunk stories written by diverse healthcare students, academics, teams and indigenous leaders in over four different languages from around the world, in addition to four commentaries, two enditorials, and a prologue to open the entire volume.

Putting together Healthpunk Vol 2 has been nothing but a joy and privilege yet again and we certainly hope you will enjoy reading it just as much. It has been wonderful to delve into all the stories that were submitted to the volume and work with the different authors and commentators that have contributed to this volume, including occupational therapists, physiotherapists, students enrolled in CoPEH-Canada's 2022 hybrid course on Ecosystem approaches to health, PhD students in health and society, critical healthcare scholars, political economists, public health scholars, indigenous leaders, bodyworkers, speech and language pathologists, and the list goes on.

And how else would we work but together and across all sorts of disciplinary and sectorial boundaries given the complex social, environmental and health challenges we are facing today? The work that has been done for Healthpunk Vol 2 is some of the most difficult, yet some of the most pertinent: The imagining of futures that not only challenge the status quo but help us see and navigate toward possibilities for more ecologically and socially responsible Eco/health/care futures.

Now it is over to you, dear readers, to take the journey with us over to that other side that this new collection of healthpunk stories is steering us toward. We hope you will enjoy the ride, and maybe take a few others along with you!

Healthpunk Vol 2: Fiction + Healthcare + You is available for reading and to download here, free of charge.

399 Hits

- 19 OCTOBER 2022

by Jena Webb, Director of Programmes, CoPEH-Canada

October 20, 2022

I recently represented CoPEH-Canada in a project to uncover, describe and systematize best practices for integrating sex and gender (s/g) into integrated knowledge translation (iKT) projects in the fields of occupational and environmental health with the CIHR funded team GESTE (French acronym for “Gender, Environment, Health, Work and Equity”). Among other research activities, we carried out a critical evaluation of the inclusion of sex, gender, and integrated knowledge translation in graduate research projects following the 2018 CoPEH-Canada hybrid course (Vansteenkiste, Saint-Charles and Fillion, 2019). I was also involved in a scoping review of the scientific and grey literature that described such practices. After removing doubles from a second search of scientific databases, we were left with 399 hits. This blog describes my personal journey screening those 399 articles.

Through reading the 399 abstracts, I was struck again and again by the multiple injustices that are handed to people, primarily women and non-binary people. Mid-way – in the Ks – I was learning about the European Union’s system to offload refugee screening to Morocco and the sexual violence that the men in charge of checkpoints inflict on refugee women (Keygnaert, et al. 2014). After 75 pages of abstracts on knowledge mobilization in studies on health, equity and gender I came across the first sentence that got to the root of the injustice: “They [the men in charge of checkpoints] seem to proceed in impunity.”

They seem to proceed in impunity.

Such a short sentence. With so much meaning. First, the emphasis was finally removed from the victim and placed on the perpetrator. At last. But, like we do in academia, it was done meekly, hedged. They seem to proceed in impunity.

Later, while I was reading the full articles we had retained from the second screening (n=59), toward the end, in the Ss, I began the only full article yet that dealt explicitly with men’s health, an article about African American men’s experiences with prostate cancer. Here, I read that one of the common supportive themes for these men were the women in their lives (Schoenfeld and Francis, 2016). I had just finished reading 26 articles about women’s health and not one of the articles pointed to the men in their lives being a supportive factor. And here, one of their three main findings was that in order to reach the men, you have to go through the women.

Floored.

Working with women in order to reach men was one of the most recommended solutions offered in this paper. “Repeatedly informants told us that “women [are the ones who] talk about preventative care. We tell everything, you know. And share everything,” and that “[women are] the ones who push their husbands ... to make appointments and so forth” (Schoenfeld and Francis, 2016, p11).

The implications of this are two-fold. First, the women followed by the studies in this review had all these imposed health problems of their own, resulting in some cases from societal inequities begun, at least in part, at the behest of patriarchy, meanwhile, in this example, they are also assuming the responsibility of men’s health problems too.

Second, where were the men in the 26 previous full articles I read? Many of these articles were about cervical or breast cancer. Why wasn’t one of the main findings that men were a supportive structure in their healing or proactive health strategies? Not a peep about this. Nada, ziltch. Perhaps it wasn’t asked, which is in and of itself telling, but in at least one case, as I would discover soon enough, the opposite was found.

A kind of toxic masculinity was on display in this sample of 399 articles focusing on health, equity and gender. Either perpetrator or absent.

Walloped.

Another moment. Among how many moments? I’m 5 articles away from finishing the screening process. Ironically, I’m reading about cervical cancer screening among Latina immigrants. I see the finish line. I see it. This morning, maybe two coffees later, I’ll be done the screening. And I come across this sentence: “because the promotoras identified male attitudes as a barrier to screening” (Gregg et al. 2010). My reflections regarding women being the main supporting factor in men’s prostate cancer process reverberate and are shattered. I had been feeling a “weight” of patriarchy either being the root cause of the inequity-based health issues I was reading about (e.g. violence against women) or, at best, when not to blame, men were neutral (i.e. basically absent). But here I was learning that even when they could very well have played the analogous role as women in the prostate cancer study, that of support, they were a barrier. A reef. Definition of reef: a hazardous obstruction. Barrier/reef. A process of disempowerment.

Credit: Wise Hok Wai Lum. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

“A slice of truth” (term Gregg 2010 uses)

Granted, cervical cancer and prostate cancer are far from analogous. Cervical cancer can shine a light on infidelity in a couple, making it rife for conflict, a reef, whereas prostate cancer is unlinked to contentious issues and can, therefore, be a moment to come together.

Yet, then what of breast cancer?

These “399 hits” are a drop in the bucket compared to the incessant set-backs, injustices and slaps in the face dealt to women daily, for 1000s of years. 399 hits of an incalculable harm.

Time, time heals all wounds? No, that is a stance of privilege. The majority of the world is barely out of their previous hardship before the next hits. I have been comfortably reading these articles from the safety of my home during a pandemic through which I was able to continue to work. I made it through the screening. I am on the last of the 19 articles retained and needing a full reading for data extraction. I am seeking a path forward; how I can, not just be witness to this aggression, but be an agent, an authentic agent. And I am gifted these words by Nina Wallerstein, a white settler researcher from an academic, middle-class background:

- "I began to ask how can I work as a guest on this land? That perception has kept me able to be myself, to say, this is what I can offer, these are the skills I have, and to seek to be a good guest ... then I can work with integrity." (Muhammad, 2015)

We can all - men, women, non-binary people - be guests to other people’s realities. The posture of a guest, it seems to me, is one of humility, gratefulness and care.

The 19 articles retained for the scoping review can be found here:

References

Gregg, J., L. Centurion, J. Maldonado, R. Aguillon, R. Celaya-Alston and S. Farquhar (2010). "Interpretations of interpretations: combining community-based participatory research and interpretive inquiry to improve health." Progress in community health partnerships: research, education, and action 4(2): 149-154.

Keygnaert, I., et al. (2014). "Sexual violence and sub-Saharan migrants in Morocco: a community-based participatory assessment using respondent driven sampling." Globalization and health 10: 32.

Muhammad, M., N. Wallerstein, A. L. Sussman, M. Avila, L. Belone and B. Duran (2015). "Reflections on Researcher Identity and Power: The Impact of Positionality on Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) Processes and Outcomes." Critical sociology 41(7-8): 1045-1063.

Schoenfeld, E. R. and L. E. Francis (2016). "Word on the Street." American Journal of Men's Health 10(5): 377-388.

Vansteenkiste, Jennifer, Saint-Charles, Johanne, Fillion, Myriam. Évaluation de la prise en compte du sexe et du genre dans l’application des connaissances dans des projets de recherche en santé environnementale à la suite d’une formation. In: conference proceedings Le 89e Congrès de l'Acfas; 2019.

From wicked problems to wicked, awesome solutions: Introducing compound solutions

- 11 APRIL 2022

By Jena Webb, director of programmes, CoPEH-Canada

April 27, 2022

- So much of life, it seems to me, is the framing and naming of things.

- Eve Ensler, In the body of the World1

Since the term was introduced in the 1970s2, and particularly since the 1990s, researchers in numerous domains have been examining wicked problems from countless angles. Wicked problems are societal dilemmas that defy succinct definition and elude swift resolution because no trialed solutions are at hand, the system is in constant flux and solutions can trigger further problems2,3. Due to their nature, there remains much to be learned about wicked problems. Meanwhile, environmental conditions are worsening, and people have become impatient for solutions. One just has to look to the diversity of citizen-driven initiatives for change collected online to get a taste of the hunger for solutions that is out there[i].

In the same period, the term ‘solutions’ has gotten a bad reputation. Between cookie-cutter interventions applied write-large (such as ‘import substitution’4, impractical techno-fixes (such as carbon capture and storage5) and solutions which beget new problems (such as pesticides6) one can see why some people are wary of embracing the term.

The problem is, there is no adequate alternative. ‘Response’ is the most common substitute. But putting one’s head in the sand is a response to climate change; it just isn’t a very constructive one. In fact, it is quite harmful. Responses can be positive or negative; passive or active. Solutions are intended to be positive and active.

The Oxford dictionary defines a solution as ‘A means of solving a problem or dealing with a difficult situation.’

Unfortunately, the ‘science of solutions’ is considerably less well advanced than the techniques we use to diagnose wicked problems, which include ecosystem approaches to health, systems science, post-normal science, ecohealth, onehealth, discourse analysis and so on7–10. This piece provides novel nomenclature which can serve as common language to rally researchers, practitioners, citizen’s groups and politicians around positions and actions which aide in the present human endeavour to restore and improve the state of our environment and, concomitantly, our health, while maintaining productive livelihoods.

Compound solutions

There appear to be interventions - or wicked, awesome solutions - which respond to multiple complex problems simultaneously. To grasp how they manifest, one can imagine these ‘wicked, awesome solutions’ like the compound eyes of insects, the compound leaves of some tree species or the compound flowers of some plants in that the ramifications of the initiative are manifold. Each ‘compound solution’ is composed of its own unique set of complex issues which it inherently impacts. Compound leaves, such as those of an ash tree or a walnut tree, are in fact composed of many leaflets grouped together on a common stem (see Figure 1). If the entire compound leaf structure were considered to be a compound solution, then each individual leaflet could be seen as the wicked problems that this solution zeros in on. Compound solutions, like the wicked problems that they address, are multifactorial.

To give a few examples, first, urban agriculture (Figure 1) has the potential to alleviate issues related to several complex problems at the intersection of society, health and urban ecosystems, including: food insecurity, green house gas emissions, air pollution, access to nature, physical activity (obesity, diabetes, etc.), urban biodiversity, land degradation, heat islands, runoff and more11. To give another example, reducing food waste would allow us to attack some of the same wicked problems as urban agriculture and also improve waste management12.

Agroforestry has the advantage of bringing in economic resilience through diversification of end products while insuring conservation, reduced erosion, regional-scale biodiversity, corridors and carbon sequestration13.

Traditional foods address some of the same wicked problems as above, but in rural settings and have the added value of valorizing Indigenous culture and the health benefits for First Nations people that come along with that14,15.

As another example, active transportation responds to multiple complex problems in urban settings by reducing air pollution, making cities safer, increasing physical activity and access to green spaces, decreasing greenhouse gases, noise pollution and stress related to traffic congestion, etc.16.

Figure 1: Urban agriculture compound solution

By combining multiple compound solutions, each remedying its own set of wicked problem, we begin to see how this strategy could go a long way toward improving major social, health and environmental issues. As with ecosystems17 and economies4, the dynamic stability of the ‘system of solutions’ should increase with diversity. It is thus the diversity of compound solutions which becomes important. The greater the ‘diversity’ of wicked problems addressed in each compound solution or by a set of compound solutions working together in a locality, the further we get toward our goal of a sustainable future.

Two other factors, in addition to diversity, will broaden the scope of compound solutions: replication and scale. ‘Replication’ occurs when local-scale compound solutions are applied independently in multiple sites. The value added of this approach is more than simply the sum of the benefits of each compound solution. As with isolated communities of species evolving in separate environments, compound solutions should be adapted to the local reality, allowing for emergent properties. These emergent properties will allow the solution to respond to more of the wicked problems present in the area.

Concurrently, compound solutions of a different scale – a global scale – are necessary. These are solutions that require joint action by multiple players across regions. Bales18 has shown how modern slavery is contributing to ecocide. He estimates that if the nearly 30 million modern slaves and their owners constituted a country, it would be the third largest CO2 emitter in the world18. The elimination of modern slavery would be an example of a global compound solution. By eliminating modern slavery, we would address issues surrounding, justice, racism, poverty, malnutrition, climate change, biodiversity, global pollutant emissions such as mercury, and much more. So it takes a network of diverse local- and global-scale compound solutions to approximate a total solution.

Working further with the analogy of a compound leaf, if each compound solution applied locally is a compound leaf, then the set of compound solutions applied in a locality is a tree. Each locality has its own tree with the particular set of compound solutions that are being implemented there. The replication of compound solutions in different combinations across the territory makes up a ‘forest of solutions.’ The global-scale compound solutions traverse the forest as a stream or river might, with the smaller tributaries representing the wicked solutions being tackled. It is an interconnected system of diverse compound solutions that makes a healthy and dynamic ‘solution ecosystem.’

Figure 2: Forest and stream

Wicked, awesome solutions are just one class in a landscape of other ‘solution-types.’ There are also single-issue solutions, which are no less important for being focused on a single problem. Let’s call them boulders, or the bedrock in our task to improve the health and wellbeing of humans and ecosystems. An example would be finding an alternative to dumping waste water from oil exploration directly into an Amazonian river. This would be a crucial step to cleaning up said river19–21, but it does not address other issues in the region such as climate change, indigenous rights, poverty, deforestation, inequity, malnutrition, etc.

Yet another solution-type are the paradigm shifts that will need to occur to tackle root problems, or upstream drivers, as we roll out single-issue and compound solutions to wicked problems. These paradigm shifts have been referred to as ‘strategic solutions’ or ‘meta-solutions’22. Perhaps the analogy of a compound eye is best suited to illustrate the interaction of problem and solution-type (Figure 3). The given compound solution, in this case active transportation, works singlehandedly to alleviate some aspects of the wicked problems that constitute the photoreceptors of the compound eye. But the ‘photoreceptor-wicked problems’ all focus in on one or a few root problems, such as overconsumption, inequity, greed, individualism, etc. Meta-solutions, or paradigm shifts, would be required to neutralize the root problems.

Figure 3: Compound solutions, wicked problems and root problems

Several decades of research has led us to a pretty good understanding of many environmental issues and their impacts on our health. Some details have yet to be worked out, and some issues are probably as yet unidentified. But in the meantime, we need to be doing what we can to improve our situation. One of the characteristics of a wicked problem is that there is no ‘stopping rule’2. That is to say, there is no way to determine if a problem has indeed been ‘solved.’ Perhaps we need to shift our goalposts. Maybe it’s not whether a certain intervention solves a given wicked problem once and for all that we should be measuring, but how many wicked problems - the ‘problem denominator’ - a given compound solution can positively impact in one fell-swoop.

Critics of the schism between environmental movements and social movements have shown that there is really only one “bus”5,23. To overcome the perceived rift between the two, we should be looking to integrate multiple ‘solution-types’ as we work together in transdisciplinary teams. To summarise, this piece has introduced the idea of local and global compound solutions which inherently have the capacity to tackle multiple wicked problems, both environmental and social, simultaneously. These compound solutions can work along side single-issue solutions and meta-solutions, aimed at bringing about paradigm shifts, to address many of the environmental and societal problems facing us at this juncture in time. The hope is that this piece provides some common language for us to come together to work on common solutions to our wicked problems. The framing of interventions as compound solutions can also be useful in “selling” them to policy makers from across distinct departments for subsequent co-creation of best practices. There is great potential for transdisciplinary teams to coalesce around compound solutions and to support their implementation toward a common sustainable future.

References

1. Ensler, E. In the Body of the World. (Metropolitan Books, 2013).

2. Rittel, H. W. & Webber, M. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sci. 4, 155–169 (1973).

3. Conklin, E. J. Dialogue mapping: building shared understanding of wicked problems. (Wiley, 2006).

4. Jacobs, J. The Nature of Economies. (Random House, 2000).

5. Klein, N. This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate. (Knopf Canada, 2014).

6. Carson, R. Silent Spring. (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1962).

7. Houle, K. L. F. Responsibility, Complexity, and Abortion: Toward a New Image of Ethical Thought. (Lexington Books, 2013).

8. Saint-Charles, J. et al. Ecohealth as a Field: Looking Forward. EcoHealth 11, 300–307 (2014).

9. Waltner-Toews, D. & Wall, E. Emergent perplexity: In search of post-normal questions for community and agroecosystem health. Soc. Sci. Med. 45, 1741–1749 (1997).

10. Webb, J. C. et al. Tools for thoughtful action: The role of ecosystem approaches to health in enhancing public health. Can. J. Public Health. 101, 439–441 (2010).

11. Cribb, J. H. J. The coming famine: The global food crisis and what we can do to avoid it. (University of California Press, 2010).

12. Stuart, T. Waste: Uncovering the Global Food Scandal. (Penguin Books, 2009).

13. Schroth, G. & McNeely, J. A. Biodiversity Conservation, Ecosystem Services and Livelihoods in Tropical Landscapes: Towards a Common Agenda. Environ. Manage. 48, 229–236 (2011).

14. Kuhnlein, H. V. & Receveur, O. Dietary Change and Traditional Food Systems of Indigenous Peoples. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1996 16, 417–442 (1996).

15. Kuhnlein, H. V., Receveur, O., Soueida, R. & Egeland, G. M. Arctic Indigenous Peoples Experience the Nutrition Transition with Changing Dietary Patterns and Obesity. J. Nutr. 134, 1447–1453 (2004).

16. Giles-Corti, B. et al. Translating active living research into policy and practice: One important pathway to chronic disease prevention. J. Public Health Policy 36, 231–243 (2015).

17. Abrams, P. A. Is Predator-Mediated Coexistence Possible in Unstable Systems? Ecology 80, 608–621 (1999).

18. Bales, K. Blood and Earth: Modern Slavery, Ecocide, and the Secret to Saving the World. (Spiegel & Grau, 2016).

19. Webb, J., Coomes, O., Mainville, N. & Mergler, D. Mercury Contamination in an Indicator Fish Species from Andean Amazonian Rivers Affected by Petroleum Extraction. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 95, 279–285 (2015).

20. Webb, J., Coomes, O. T., Mergler, D. & Ross, N. Mercury Concentrations in Urine of Amerindian Populations Near Oil Fields in the Peruvian and Ecuadorian Amazon. Environ. Res. 151, 344–350 (2016).

21. Webb, J., Coomes, O. T., Mergler, D. & Ross, N. A. Levels of 1-hydroxypyrene in urine of people living in an oil producing region of the Andean Amazon (Ecuador and Peru). Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 91, 105–115 (2018).

22. Prugh, T. Childhood’s End. in State of the World 2015: Confronting Hidden Threats to Sustainability (ed. The Worldwatch Institute) 129–140 (Island Press/Center for Resource Economics, 2015).

23. Hawken, P. Blessed Unrest: How the Largest Movement In the World Came into Being and Why No One Saw it Coming. (Viking Press, 2007).

Biographie Margot Parkes

- 03 NOVEMBER 2021

Margot Parkes est professeure à l'école des sciences de la santé, nommée conjointement au programme de médecine nordique de l'Université du Nord de la Colombie-Britannique et professeure honoraire au département de médecine préventive et sociale de l'Université d'Otago, à Aotearoa/Nouvelle-Zélande. Elle est née à Aotearoa/Nouvelle-Zélande et a le privilège de vivre, de travailler et d'apprendre sur le territoire Lheidli T'enneh, dans le nord de la Colombie-Britannique, depuis 2009. Dans tous ses travaux, Margot travaille avec d'autres personnes - dans tous les secteurs, toutes les disciplines et tous les contextes culturels - pour améliorer la compréhension de la terre, de l'eau et des systèmes vivants (écosystèmes) en tant que fondement de la santé et du bien-être. Les recherches de la Mme Parkes relient les déterminants sociaux et écologiques de la santé, en particulier dans les communautés rurales, éloignées et indigènes, en mettant l'accent sur les approches intégratives, en partenariat et informées par les indigènes. Elle est co-responsable fondatrice de la Communauté de pratique canadienne sur les approches écosystémiques de la santé (CoPEH-Canada) et co-directrice de recherche du réseau de l'Observatoire Environnement, Communauté, Santé, un réseau pancanadien et international. Le réseau ECHO se concentre sur les impacts cumulatifs sur la santé des défis complexes en matière de santé, d'équité et d'écologie liés à des questions telles que l'extraction des ressources, le changement climatique et la gouvernance des bassins versants.

Biographie Jena Webb

- 03 NOVEMBER 2021

Au cours des deux dernières décennies, le travail de Jena Webb, tant au niveau national qu'international, a porté sur les liens entre la santé, la société et les écosystèmes. Sa formation a commencé en sciences naturelles au baccalauréat en biologie et à la maitrise en sciences de l’environnement, mais lors de son doctorat elle a fait une étude qui chevauchait la géographie physique et la géographie humaine et portait sur un regard genré des impacts de la déforestation et de l'extraction pétrolière en Amazonie sur les niveaux de mercure et d'hydrocarbures dans les poissons et les peuples autochtones qui les consomment. Elle est actuellement l'une des principales collaboratrices dans le cadre du projet de recherche GESTE - pour le partage des connaissances (Genre Équité Santé Travail Environnement). Dans son rôle actuel de Directrice des Programmes de CoPEH-Canada, elle dirige les communications et codirige le réseautage et l'enseignement.

Biographie Johanne Saint-Charles

- 03 NOVEMBER 2021

Le travail de Johanne Saint-Charles concerne les liens entre la santé, l'environnement et la société avec une attention particulière pour le genre et les inégalités sociales. Elle fait partie des membres fondatrices de communautés de pratique en écosanté en Amérique latine et au Canada, et elle a contribué à la chaire de recherche Ecosanté sur la pollution urbaine en Afrique de l'Ouest. Elle a toujours considéré qu'il était important de soutenir les chercheuses et chercheurs émergents par le mentorat et des possibilités de travailler sur des projets collaboratifs. Elle a mis sa formation disciplinaire en communication et en réseaux au service d'équipes transdisciplinaires qui étudient les déterminants de la santé tout en cherchant à concevoir des réponses durables aux problèmes de santé et aux disparités. Elle est actuellement directrice de l'Institut Santé et société.

Johanne Saint-Charles bio

- 03 NOVEMBER 2021

Dr. Johanne Saint-Charles' work concerns the links between health, the environment and society, with a focus on gender and social inequities. She is among the founding members of communities of practice in ecohealth in Latin America and Canada, has contributed to the Ecosanté Research Chair on urban pollution in West Africa. She has always considered supporting emerging researchers through mentorship and opportunities to work on collaborative projects crucial. She puts her disciplinary background in communication and networks to use in transdisciplinary teams looking at determinants of health while seeking to design sustainable responses to health issues and disparities. She is currently director of l’Institut Santé et société at the Université du Québec à Montréal.

Margot Parkes bio

- 03 NOVEMBER 2021

Margot Parkes is a Professor in the School of Health Sciences, cross-appointed in the northern Medical Program at the University of Northern British Columbia and is also an honorary Professor at the Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, at the University of Otago, in Aotearoa/New Zealand. She was born in Aotearoa/New Zealana and has been privileged to live, work and learn on Lheidli T’enneh Territoryin northern BC since 2009. In all her work, Margot works with others – across sectors, disciplines and cultural contexts – to enhance understanding of land, water and living systems (ecosystems) as foundational for health and well-being. Dr. Parkes’s research connects social and ecological determinants of health, especially in rural, remote and Indigenous communities, with a focus on integrative, partnered and Indigenous-informed approaches. She is founding co-lead of the Canadian Community of Practice in Ecosystem Approaches to Health (CoPEH-Canada) and also research co-lead of the Environment, Community, Health Observatory Network, a pan-Canadian and international network. The ECHO Network focuses on the cumulative health impacts of complex health, equity and ecological challenges of issues such as resource extraction, climate change and watershed governance.

Jena Webb bio

- 27 OCTOBER 2021

For the past two decades, Jena Webb's work, both nationally and internationally, has focused on the links between health, society and ecosystems. Her training began in the natural sciences with a B.S. in biology and an M.S. in environmental science. During her Ph.D. she conducted research that straddled physical and human geography, focusing the impacts of deforestation and oil extraction in the Amazon on mercury and hydrocarbon levels in fish and the indigenous peoples. She is currently one of the main knowledge users in the GESTE research project - for knowledge sharing (Gender, Health, Work and Environment). In her current role as Program Director of the Canadian Community of Practice in Ecosystem Approaches to Health (CoPEH-Canada), she leads communications and co-leads networking and teaching.

Blog

- 02 NOVEMBER 2020

|

|

|

|

CoPEH-Canada is pleased to present, along with our colleagues, Healthpunk Vol2. Ten stories, four commentaries and two enditorials share visions in which the work of health and care is deliberately focused on responding to social and ecological challenges and supporting healthier ways of living. |

A hard-hitting, personal journey through a scoping review on health and gender equity. |

From wicked problems to wicked, awesome solutions: Introducing compound solutions This blog provides novel nomenclature which can serve as common language to rally researchers, practitioners, citizen’s groups and politicians around positions and actions which aide in the present human endeavour to restore and improve the state of our environment and, concomitantly, our health, while maintaining productive livelihoods. |

Tamped down or spruced up? How we ran a field course on health and ecosystems online during a pandemic

- 02 NOVEMBER 2020

|

|

The CoPEH-Canada hybrid course and webinar series on Ecosystem Approaches to Health is a part online, part face-to-face graduate level course offered each year in May at four “sites”: Montréal (UQAM), Guelph (University of Guelph), Prince George (University of Northern British Columbia) and an online “site.” Eight two-hour sessions are conducted as simultaneous webinars across the sites. The rest of the time for the three onsite groups are locally run sessions. We offer a rigorous, hands-on pedagogical approach. The course is available to graduate students from all disciplines and also to professionals interested in these themes. An experienced, pan-Canadian team presents innovative and dynamic approaches for better understanding the multiple factors which influence health on issues at the confluence of health, the environment and society. |

It was March 2020. We were deep into the nitty-gritty of planning for our annual hybrid field course on ecosystem approaches to health (see side bar), which we’ve been running since 2008. It was the moment where we begin contacting community groups for field visits. But would we be able to go into the field in May considering the worsening state of the Covid-19 pandemic? June maybe, but May? Was it ethical to ask already strapped community groups to commit to and prepare for something that might not happen?

Questions arose about whether we should cancel this year’s course. After all, it is a FIELD course. We called a brainstorming session amongst our seasoned course planning team, and left emboldened by the possibilities. In this blog we discuss some of the innovative teaching tools and activities that we used to *replace* the field component while still providing access to a variety of voices and perspectives and a connection to place and the land.

DIALOGUE AMONG COURSE PARTICIPANTS

Our hybrid course attracts students and professionals from an array of fields and epistemological backgrounds. We always include space for dialogue in our courses, but this year we decided to increase the webinar time by a half an hour. This half an hour was dedicated to exchange across sites and between participants. Some of these were open discussion periods on the topic of the day and others were slightly more structured activities on a given topic. For example, in addition to having students develop a poster on their project from an ecosystem approaches to health perspective and getting written feedback from their peers, this year we included a “speed dating” activity where, in break-out rooms of three people, they presented their poster in 2 minutes with time for discussion at the end. Technological challenges getting into breakout rooms cut into some groups’ time, but other groups had sufficient time to learn about someone’s work that they wouldn’t have otherwise. In the ‘lessons learned’ category, we found that these sorts of activities need to have ample time allocated to movement and glitches.

NARRATIVE READINGS

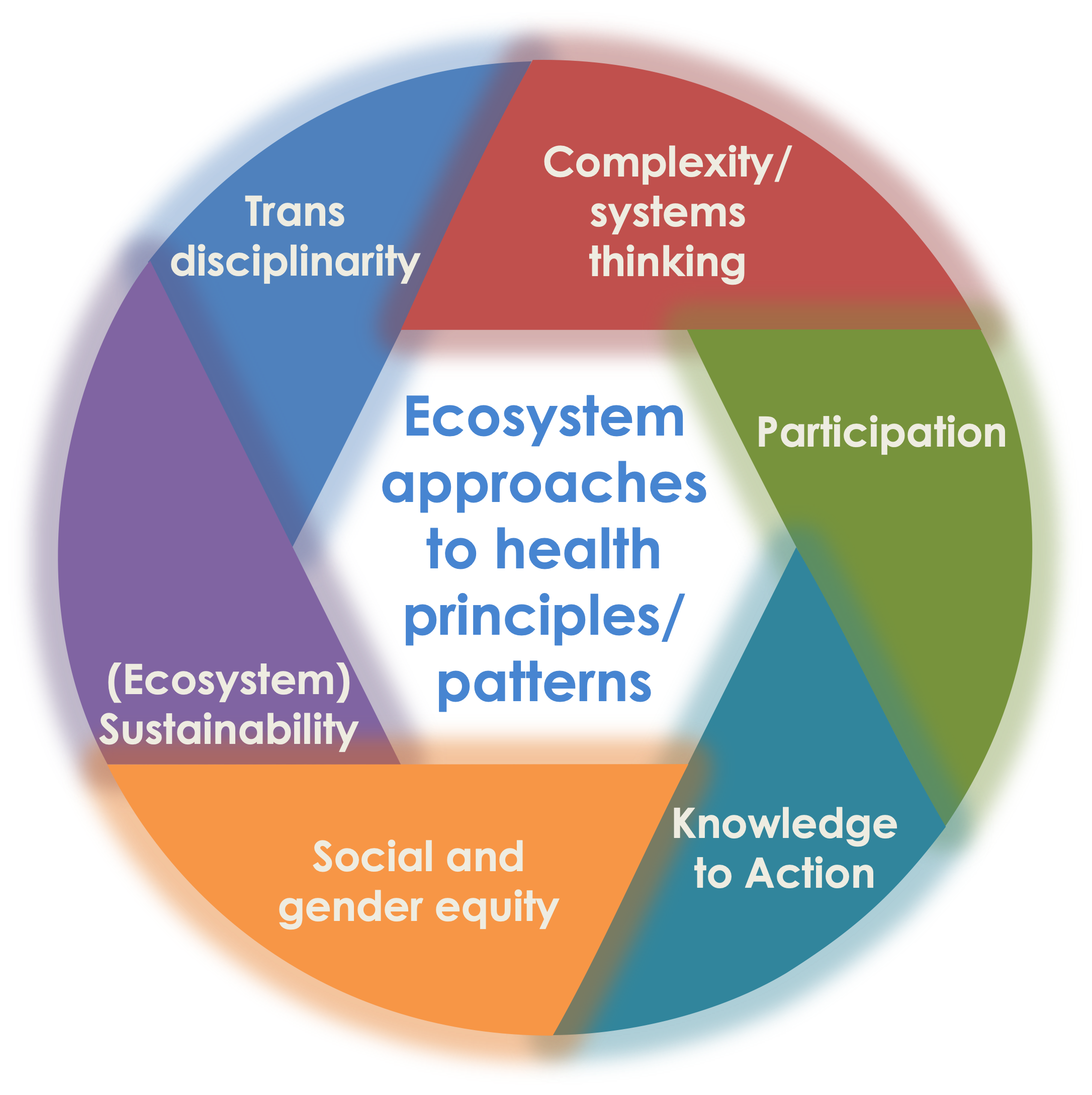

One of the principles or patterns of Ecosystem Approaches to Health is transdisciplinarity. In general, transdisciplinarity encompasses inviting different ways of thinking into our lives and work.

In light of this, we encouraged participants to engage with the narrative form during the course, providing new perspectives despite the context of confinement where we were not able, in the end, to interact in the field. We pre-selected books - novels and poetry - for participants to engage with before and throughout the course.

These books all have to do, to greater and lesser extents, with the course theme - the health of humans and other species in their watershed. The place-based nature of some of the books, set in regions roughly around the four "sites" with an "international" focus representing the webinar group, helped us replace some of the land-based learning that usually occurs in our field course.  2020 CoPEH-Canada hybrid course on ecosystem approaches to health fiction reading list

2020 CoPEH-Canada hybrid course on ecosystem approaches to health fiction reading list

During one of the webinars we hosted a "book club" to exchange what we learned/reinforced through the readings. Break out rooms for each book were created and a rich discussion followed. In the debrief of the full course, one of the university sites mentioned that the narrative reading was one of the most enriching aspect of the course, but that it wasn’t “capitalized” on enough throughout the course. We are now exploring ways to make the most of this exercise and have decided to keep it even if the course goes back into the field in 2021. We are currently drawing up the list for 2021, and we would like to increase the diversity of voices represented.

INDIVIDUAL FIELDTRIPS

In lieu of going into the field together, we asked participants to make directed forays into grocery stores and parks. Here is an example of what we asked the students to do on a trip to the grocery store (or other store) (and only if they were going out anyway). We suggested that they be creative and take “evidence” (photos, drawings, audio tracks, examples of new products,) in a safe and respectful manner.

The following week we had a conversation about the students' observations.

|

Ask yourself the following questions [at the grocery store] and think about possible answers.

|

EXPLORING THE COMMON EXPERIENCE OF THE PANDEMIC

In our hybrid course on ecosystems and health, we usually develop learning through a case study in the field. Recently, our case studies have focused on the health of humans and other species in the watershed. Each site developed their own case study, but the issues raised in each location were relatively similar, creating a “common experience” within and even across sites. For 2020 we selected the ‘shared experience’ of COVID-19. We usually end the course with the presentation of a group artifact or rich picture map, a project that groups of students work on together to present their learning over the course of the month. This year we asked them to work together to explore and reflect on the ecosystem approaches to health principles through a “synthesis activity” based around COVID-19. We invited three researchers, Mélanie Lefrançois (UQAM), Samira Mubareka (Sunnybrook Research Institute) and David Waltner-Toews (U. Guelph, CoPEH-Canada elder), to comment on the students’ presentations.

The students rose to the occasion, working across platforms, time zones and language barriers to present us with three very insightful takes on links between the pandemic and ecosystem approaches to health.

The title slide of one of the three “synthesis” presentations by student groups participating in the 2020 CoPEH-Canada hybrid course on ecosystem approaches to health

The title slide of one of the three “synthesis” presentations by student groups participating in the 2020 CoPEH-Canada hybrid course on ecosystem approaches to health

GOING AGAINST THE GRAIN

As teachers, we know how hard the transition to online learning has been in most contexts. We, in no way, advocate for a whole-scale virtual transition in learning. Much is lost in the cloistering away of courses into the internet: connection with land, human warmth, spontaneous learning amongst students, intuition, attention and concentration. We do believe, however, that it is possible, if necessary, to bring some field-oriented classes online and to do it successfully; context matters.

First, hats off to our students, who embarked on this journey with us, rolled with it, and sometimes humored us and our efforts to innovate. They are really the ones who made the course a success. As graduate level students and professionals their level of enthusiasm was perhaps higher than for some other student groups. Further, since this was a graduate level seminar at the three universities, the “for-credit” groups were small, averaging around 8 students, which makes for more fluid exchanges.

Another factor contributing to our positive experience is the long-standing teaching relationship between collaborators on this course, including good communication, trust and a bank of collectively designed activities to lean on[1]. This raises the question, though, to what extent this type of relationship and trust can be constructed online. When we first started working together on these courses 12 years ago many of us did not know one another and came from various disciplinary background. We had numerous face-to-face meetings and workshops in which we negotiated in order to create a course that would not be a disconnected hodge-podge of expertise. This was done during the formal meetings, but also at breaktime or over lunch or dinner. We learned not only to trust our colleagues’ expertise, but also to trust them as people, period. Can this happen on-line?

We sincerely hope that next year the world will be a safer, healthier place and that we won’t need to run our course online. But in either case, we will be ready with the interactive and innovative ways to learn about ecosystems and health that we trialed this year, namely more time for exchange, including fiction in our teaching, reflexive exercises and coalescing around a shared experience.

[1] If you are interested in learning more about our teaching style and activities we have collected some of our materials into a teaching manual.

History

- 16 MARCH 2016

The emergence of a community of practice (CoP) begins with an idea –a belief that something new, something better should exist. CoPEH Canada began with dozens of Canadian and International connections, and 10 core members who initially came together to embark on a journey- a journey of renewal, and a journey which focuses on transforming theory into action.

Early opportunities for funding were available from the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), which enabled a creative period fueled by the aspiration for a better future- for both human society and ecosystems.

A summary of our history:

2008: We established ourselves as a Community of Practice, setting up an inter-institutional, pan-Canadian effort; focusing on defining the theory and practice of "Ecohealth" (executive summary) and hosting our inaugural fieldschool (UBC)

2009: Second fieldschool at University of Guelph

2010: First bilingual fieldschool (UQAM); began outreach to policy makers; ecosystem approaches to health was nominated as a Canadian Public Health Milestone

2011-2012: Development of career-building initiatives; creation of an “Ecosystems Approach to Health” teaching manual; innovation of Workshop + fieldschool format; fieldschools at UNBC (2011) and University of Moncton (2012, bilingual)

2013: Initiation of two new Projects- 1) Ekosanté (a collaboration with the Latin American Community of Practice (CoPEH-LAC) funded by IDRC) & 2) “Linking Public Health, Ecosystems, and Equity through Ecohealth Training and Capacity Building” (funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada [PHAC]); Workshop+fieldschool at UNBC

2014: Host of EcoHealth 2014 in Montreal; Workshop+fieldschool at York University

2015: bilingual workshop+fieldschool at UQAM

2016: Memorandum of Understanding signed between 6 universities

2017: CoPEH-Canada members receive two CIHR team grants (ECHO and GESTE pour la partage des connassainces) which will contribute to CoPEH-Canad activities

2018: CoPEH-Canada celebrates its ten-year anniversary. We held an informal 10-year anniversary social event gathering around 15 CoPEH-Canada members who had traveled to Cali for the EcoHealth 2018 conference.

2016-2020: Hybrid, multi-site course on ecosystem approaches to health. This part online, part face-to-face graduate level course on ecosystem approaches to health is offered each year in May at four “sites”: Montréal (UQAM), Guelph (University of Guelph), Prince George (University of Northern British Columbia) and an online “site.” Seven two-hour sessions (eight in the case of the online group) are conducted as simultaneous webinars across the sites. The rest of the time for the three onsite groups will be locally run sessions, including field trips (conditions permitting).

2020: Innovation of virtual experiential learning technics. A tool for putting these and similar technics into practice will be available soon.

CoPEH-Canada is witnessing our alumni and team members flourish in their activities and feels both pride and commitment regarding the long-term and resilient statement profiled on our website:

« CoPEH-Canada is an adaptive community of scholars and practitioners dedicated to the understanding, teaching and application of ecosystem approaches to address current challenges to a healthy and sustainable global future.»

Ecosystem approaches to health...

- 16 MARCH 2016

- seek to understand and promote health and wellbeing (of humans, animals and ecosystems) in the context of complex social-ecological systems, focusing on the interplay between health in the strict sense of the word, the social determinants of health, and ecosystem sustainability.

- Provide a theoretical framework and associated methodologies that are effective for dealing with complex, environmental, social and health issues interacting at various geographical and temporal scales.

- Build on participatory research practices to guide the integration of disciplines and types of knowledge, to strive for social and gender equity, and to move toward appropriate action.

- Are recognised as a ‘Milestone in Canadian Population and Public Health research’ by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Canadian Public Health Association.

- We acknowledge that similar approaches have long been understood by Indigenous colleagues and communities.

Ecosystem approaches to health Pattern Wheel © 2016 by CoPEH-Canada (original design: Sherilee Harper; ecohealth principles: Dominique Charron, 2012) is licensed under CC BY 4.0

CoPEH-Canada structure and team

- 14 MARCH 2016

CoPEH-Canada is a dynamic group of researchers and practionners. Members of the CoPEH-Canada core team come from eight universities and organizations across Canada, in various fields. Graduate students and young professionals, many of whom have taken the CoPEH-Canada field school or workshop, form a particularly dynamic sub-group, Emerging Scholars and Professionals (ESaP).

Memorandum of Understanding for the creation of a consortium for the CoPEH-Canada

In 2016, the authorities of six Canadian universities (Dalla Lana School of Public Health (University of Toronto), Simon Fraser University, Université de Moncton, Université du Québec à Montréal, University of Northern British Colombia and York University) signed a MOU for the creation of a consortium linked to the CoPEH-Canada. Since, two universities have joined: l'Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS) and Guelph University. This MOU was resigned in 2021. If you think that your institution would be interested in joining the MOU please This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. Our development is progressive, through the addition of ever more colleagues, partners and collaborators as time goes on. CoPEH-Canada works to support regional groups in Canada and also collaborates with Latin American, African and Asian partners.

- Read our five-year (2016-2020) report here.

Our core group members coordinate the pan-Canadian community of practice. The principal functions of this coordinating group are to organize the CoPEH-Canada workshops and annual ecosystem approaches to health field school, make decisions on the general management of the community, plan annual national activities, provide support to members and stimulate participation. Reactions to national-level interests and topics are responded to at this level (see our news and twitter feeds).

The director of programmes is responsible for ensuring the maintenance of basic CoPEH-Canada programmes and exploring opportunities in line with priorities established by consortium members.

Director of Programmes

|

|

Jena Webb |

Founding co-leads

|

|

|

Margot Parkes |

Johanne Saint-Charles |

Co-leads

|

|

|

|

Martin Bunch |

Maya Gislason |

Jane Parmley |

|

|

|

| Blake Poland Associate Professor, Dalla Lana School of Public Health University of Toronto |

Céline Surette Director and Professor, Département de chimie et de biochimie Université de Moncton |

Cathy Vaillancourt Professor, Institut Armand Frappier INRS |

In Memoriam

Bruce Hunter, a founding member of CoPEH-Canada, passed away suddenly on October 19th 2011. His insights, calm, wisdom and dedication to the “kids” are sorely missed by us all. He has left his mark on each of us individually and on CoPEH-Canada as a whole.

About Us

- 14 MARCH 2016

CoPEH-Canada is a community of scholars and practitioners dedicated to the understanding, teaching and application of ecosystem approaches to address current challenges to health and sustainability.

The Community of Practice, CoPEH-Canada, aims to develop Ecosystem Approaches to Health through:

- Training and capacity building

- Ecosystem Approaches to Health research and practice in Canada

- International Field Building in Ecosystem Approaches to Health

- Evaluative Research

Click here to download a summary of our ongoing contributions and key areas of action.